February 11, 2019

Randi Frank

Office on Smoking and Health

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, Mail Stop S107-7 Atlanta, GA 30341

Re: Request for Information on Advancing Tobacco Control Practices to Prevent Initiation of Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults, Eliminate Exposure to Secondhand Smoke, and Identify and Eliminate Tobacco-Related Disparities (Docket No. CDC-2018-0115)

Dear Ms. Frank:

Counter Tools works to empower communities to become healthier places, starting with the retail environment. We focus on assisting state- and local-level partners in the effort to reduce the

detrimental impact of products like tobacco at the consumer’s point of exposure and access: the retail environment.

These comments are based both on insights we have gleaned working with a variety of partners across over 20 states, who are at various stages in the progression of their tobacco control efforts, as well as on scientific evidence. Many of our partners wear many hats and work across the spectrum of tobacco control.

- What innovative strategies are working in communities to prevent tobacco use among youth, especially in terms of flavored tobacco products and e-cigarettes?

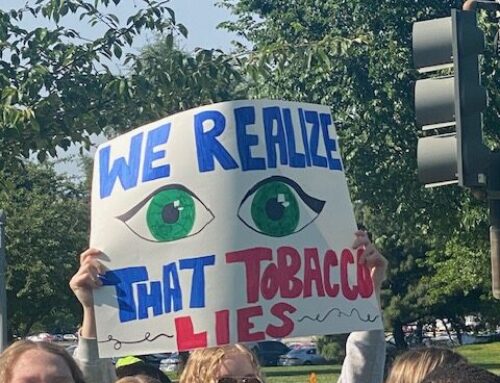

- Conducting store assessments can serve as a form of media literacy for youth, alerting them to the tactics that tobacco companies utilize to recruit them as new users. Both youth and adults involved in the experience of store assessments often become passionate advocates for change and are able to speak to what they see in stores all across their communities. The data gathered from these assessments can also be valuable in advocating for policies that can prevent youth tobacco use. For example, store assessment data can showcase the widespread availability of cheap, flavored tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, and when combined with mapping data, including at stores near schools.

- How can CDC support state and local health departments and their partners to improve community engagement with populations most at risk for tobacco use?

- CDC can continue to bring attention to environmental influences that contribute to current disparities in tobacco use. This includes disparities in the retail environment in low-income communities and communities of color as it relates to tobacco retailer densityi, as well as tobacco product availability, advertising, and pricing.

- CDC can help de-silo tobacco control efforts. Populations in communities most at risk may lack cessation assistance, coverage by a clean air policy, have low tobacco prices, and have a retail environment that contributes to youth initiation, continued use, and derails quit attempts. Recognizing how these factors combine to create norms around tobacco use and addressing them simultaneously in an integrated way may help to both address these disparities and help with receptivity to tobacco control efforts.

- CDC can provide funding to local groups to conduct store assessments and subsequent community education. This can help identify disparities in availability of products, pricing, availability of discounts, and the prevalence of advertising, as well as provide additional information to help communities understand some of the environmental determinants of tobacco use.

Getting community members involved in store assessments can also energize and complement other tobacco control efforts by bringing attention to the broader presence of tobacco in the community. - CDC can provide funding for state and local health departments to evaluate their efforts engaging at-risk populations and provide a platform to share those evaluation results.

- CDC can provide funding for specific positions at the state and local level for staff who are members of the populations most at risk for tobacco use to work on tobacco control.

- CDC can encourage the elevation of authentic voices and strategies that are based in the day-today reality of the most at-risk populations with stories from members of those population groups, staff coordinating coalitions who are members of that population, and coalitions with most or all members from those populations as well.

- What innovative strategies are effective in communities to decrease tobacco use in population groups that have the greatest burden of tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure?

- While there may not be long-term data on reducing tobacco use rates from this type of policy yet, all available evidence indicates that policies such as San Francisco and Philadelphia’s policies that set a cap on the number of tobacco retailers per district in order to eliminate disparities in tobacco retailer density across the city should also help to reduce disparities in tobacco use rates across the city.

- In addition, modeling data has shown that prohibiting tobacco retailers within 1000 ft of schools could nearly eliminate race- and income-based disparities in tobacco retailer density between neighborhoods.ii

- Strong minimum price laws could also help reduce disparities in tobacco use, preventing price manipulation by geographic area or by brand, thereby reducing targeting of products to certain populations. Prices for cigarettes are often lower in low-income communities, communities of color, and neighborhoods with more school-aged youth.iii Studies have shown that menthol cigarettes specifically are priced lower and more frequently discounted in African-American neighborhoods.iv Similarly, little cigars and cigarillos are often priced lower in communities with more African-American residents and more young adults.v Setting minimum prices for each type of tobacco product across a city would prevent much of this neighborhood-level price-based targeting.

- What science, tools, or resources does the public health sector need CDC to develop in order to enhance and sustain tobacco prevention and control efforts?

- Evaluation of point-of-sale policies to encourage communities to pursue these policies alongside their other tobacco control efforts as best practice. For example, an evaluation published recently in Pediatrics shows tobacco retailer licensing can help reduce youth use and initiation of both cigarettes and e-cigarettesvi. Innovative retail strategies such as the ones noted above in San Francisco and Philadelphia are also built on tobacco retail licensing systems. However, evaluation studies of these type of policies have been limited to date.

- Mapping of tobacco retailers across the country to help identify disparities.

- Ideally, this would be a national database of retailers with an interactive map of census, BRFSS, and YRBS data with the ability to show longitudinal change. CDC could fund the development of this type of map and/or recommend the creation of these maps and databases.

- To help address some of the disparities in tobacco use, the CDC could issue strong statements on equity regarding:

- Avoiding preemption, undoing preemption, and protecting local control. This is a driver of some of the geographic disparities in tobacco use across the country. While states are

working towards increasing taxes or implementing a statewide clean air law, localities can be innovating on other strategies that advance tobacco control practice. - The relationship between tobacco retailer density and smoking rates, as shown in the 500 Cities Project and other previous studies, recognizing the burden that lower income

communities and communities of color face with greater exposure to tobacco marketing and availability of tobacco products.vii

- Avoiding preemption, undoing preemption, and protecting local control. This is a driver of some of the geographic disparities in tobacco use across the country. While states are

i Lee JGL, Sun DL, Schleicher NM, et al. Inequalities in tobacco outlet density by race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, 2012, USA: results from the ASPiRE Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017;71:487-492.; Rodriguez D, Carlos HA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Berke EM, Sargent JD. Predictors of tobacco outlet density nationwide: a geographic analysis. Tob Control. 2012;22(5):349-55.

ii Kurt M. Ribisl, Douglas A. Luke, Doneisha L. Bohannon, Amy A. Sorg, Sarah Moreland-Russell; Reducing Disparities in Tobacco Retailer Density by Banning Tobacco Product Sales Near Schools, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 19, Issue 2, 1 February 2017, Pages 239–244, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw185

iii Henriksen L, Andersen-Rodgers E, Zhang X et al. (2017). Neighborhood Variation in the Price of Cheap Tobacco Products in California: Results from Health Stores for a Healthy Community. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(11), 1330-1337. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx089; Khan T, Resnick EA, Liu Y, Barker DC, Chaloupka FJ. Cigarette Pricing is Lowest in Black Neighborhoods: 2010-12. A Tobacconomics Research Brief. Chicago, IL: Tobacconomics, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2015

iv Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Dauphinee AL, & Fortmann SP. (2012). Targeted Advertising, Promotion, and Price For Menthol Cigarettes in California High School Neighborhoods. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14(1), 1116-121. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr122

v Cantrell J, Kreslake JM, Ganz O, et al. Marketing Little Cigars and Cigarillos: Advertising, Price, and Associations With Neighborhood Demographics. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(10):1902-1909. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301362.

vi Astor, RL et al. Tobacco Retail Licensing and Youth Product Use. Pediatrics Feb 2019, 143 (2) e20173536; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-3536

vii Leas EC, Schleicher NC, Prochaska JJ, Henriksen L. Place-Based Inequity in Smoking Prevalence in the Largest Cities in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. Published online January 07, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5990