Many states and localities have adopted comprehensive smoke-free laws. However, there are over 58 million Americans still exposed to secondhand smoke today. A closer look at which communities are left unprotected reveals clear health inequities and points to a need for smoke-free protections for all as a strategy to advance social justice.

The idea that exposure to secondhand smoke is dangerous is certainly not a new one. In fact, we’ve known this risk since the first Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health was issued in 1964. Today, more than 50 years later, we also know that the deaths of at least 2.5 million nonsmokers can be attributed to secondhand smoke exposure. Over the years, there has been significant progress in the smoke-free movement. What started as policies to create nonsmoking sections in places like restaurants and airplanes has evolved into comprehensive smoke-free laws covering all public places and workspaces in 27 states and more than 1,500 localities.

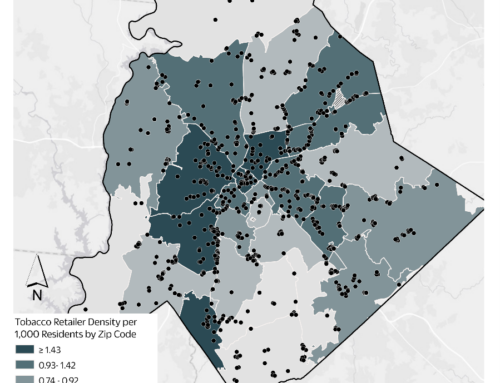

Unfortunately, despite this success, these laws still aren’t protecting all of us. In fact, 39% of Americans live in a place that is not fully protected by 100% smoke-free laws. Like many health equity issues, we see that where people live and other sociodemographic factors make a big difference in terms of exposure to secondhand smoke. Communities with higher income and education are more likely to be covered by smoke-free laws than communities with a greater African American population or more residents living under the poverty level.

Additional gaps in smoke-free protections exist, even within individual communities. Many jurisdictions with smoke-free regulations offer exemptions for certain types of businesses. Generally, these exemptions apply to venues such as factories, casinos or bars that are employing primarily low-wage workers, further harming people who are already burdened with other health and social inequalities. Interestingly, evidence from peer-reviewed studies across the country show that smoke-free policies and regulations do not have an adverse economic impact on the hospitality industry.

As another example of the link between income and secondhand smoke exposure, the CDC reports that renters, especially those who live in multi-unit housing, also face higher rates of exposure. Thankfully, in 2018, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development adopted a rule requiring all their public housing properties to implement a smoke-free policy, but there are plenty of other multi-unit housing locations across the country without a policy in place.

As we aim to advance social justice in the world of tobacco prevention and control, it’s important to work towards guaranteeing smokefree protections for all, regardless of geographic region, race, ethnicity, occupation, or economic status. The American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation has several recommendations for closing this gap, including:

- Making all workplaces smokefree– with no exceptions.

- Giving local communities back their power to create stronger smokefree policies. This involves repealing preemption where it exists.

- Prioritizing smokefree protections in health equity initiatives– and vice versa.

We’ve come a long way since 1964, but it’s clear the work isn’t done yet. This time, let’s be sure not to leave anyone behind.

This post was originally published as a feature article for The Geographic Health Equity Alliance (GHEA), a CADCA initiative. GHEA is a CDC funded National Network dedicated to reducing geographic health disparities related to tobacco and cancer.